For generations, New Zealand’s surf lifesaving clubs have stood as rugged outposts against our beautiful – but unforgiving – coastlines. Functionally, their purpose is simple: to facilitate the saving of lives. But they’re much more than that.

Over time, these buildings have become the centres of coastal communities, the hubs for generations of recreation, education, and social gatherings. Many have been there so long that they’re now viewed as iconic pieces of architecture – even if that was never the intention.

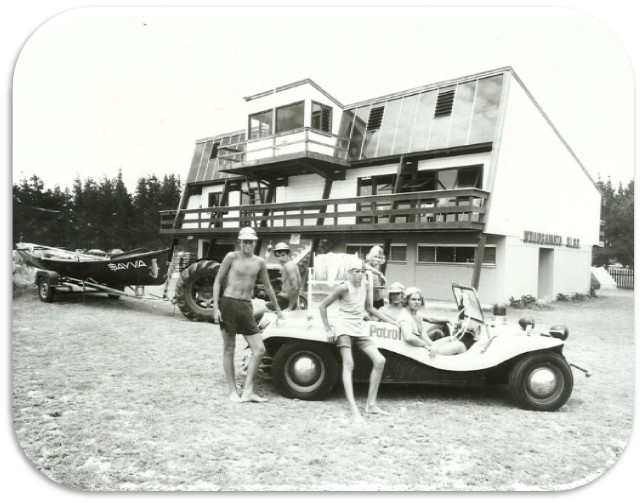

Waimarama Surf Life Saving Club / 📸 NZIA

Because they’re often the only significant manmade structure in sight, surf clubs are a reassuring presence. The red and yellow flags in summer. Lifeguards zipping about in their bright orange inflatables. The prospect of a bathroom when your kids really need to go. They’re familiar to the point that these places are just there, and it’s strange to imagine how a beach might look, or feel, without them.

But beaches are brutal environments for buildings. The wind is incessant. Sand blasts and salt corrodes. Rain drives in at impossible angles. Over time, that takes its toll. Many of the historic clubs dotted around the country were originally built in the 1950s and 1960s, and they’re now approaching a crossroads.

Designed for a different era – and often by volunteers with limited resources – these older buildings are thickly coated with nostalgia but can struggle to meet the changing operational demands and safety standards of modern surf lifesaving.

New Brighton Surf Lifesaving Club / 📸 DINZ

In recent years, clubs up and down the country have been undertaking major refurbishment projects and, from an architectural perspective, these present especially exciting and interesting (not to mention challenging) opportunities.

Examples across New Zealand – and indeed Australia where surf club culture is even more deeply embedded – over the last decade or so demonstrate there’s no one right way to design (or redesign) a surf club. Just as every beach is different, so is the building erected to watch over it. Some favour function over form. Others have a deeper architectural narrative that tries to match the local mood; golden sand to light timbers; iron sand to darker driftwood and charred finishes. Encouraging use of natural and sustainable materials is obvious, but each approach, method and material will have its merits, based on the specific needs of the club and the environment in which it sits.

Considerations must also be made for climate resilience, whether it be bigger storms and rising tides, advancing or receding dunes, or wildlife and nature restoration efforts. And budgets are inevitably constrained; while often assisted by the national surf lifesaving body and councils, individual surf clubs tend to rely heavily on volunteers, local fundraising, and corporate sponsorship to make up the (often significant) shortfall.

Lyall Bay Surf Club / 📸 Andy Spain

Then there’s visual beauty. This is a hard concept to define, but the Living Building Challenge provides a helpful guide in the idea of “beauty” in design being focused on elements that enhance the public realm – think public art and other visual features that celebrate the culture and spirit of a place.

Good design can thread all these needles, but you could argue it’s that underlying goodwill and community involvement that can have an outsized influence in the success of such projects. The more a community is engaged, the more involved it becomes, the more the project is loved, and the better the outcome can be.

After all, beaches remain one of our most egalitarian spaces. Anyone, of any age, from any walk of life, is free to go there. The surf clubs that dot those beaches may be run by, and for, members, but they serve everyone: if you’re in trouble, someone will emerge, as if by magic, from one of these iconic structures to rescue you. That’s a truly wonderful thing.

So, these projects aren’t simply about replacing outdated facilities; they’re also a chance to re-imagine the role these clubs can have within our communities. As the next chapter of New Zealand’s surf lifesaving story is written, architecture will hopefully be a feature in helping form deeper community connections and ensuring these vital institutions continue to thrive for generations to come.